Oral Histories of T.E. Cames

Oral Histories of T.E. Cames

Believed to have been born in New Orleans in late October of 1929, T.E. Cames was the only son of an illiterate mother and a boogie-woogie jazz pianist. His father, Fletcher Cames, left the family the following spring. Without work or money, his mother, Lizzie Pettway, returned to her birth place, Boykin, (Gee’s Bend) Alabama. They lived in a small cabin with her uncle, Major Pettway. Major was a widowered sharecropper with a young daughter. The daughter, who had survived a complicated birth that claimed her mother, was assumed to be Lizzie’s responsibility in the living arrangement. T.E. was expected to help in the fields. Being a whimsical child who was easily distracted; most frequently by the scraps of fabric that his mother would use to sew quilts, he often spent his time playing with what was considered women’s tasks while neglecting his masculine obligations on the farm. This did not sit well with his uncle. The resulting confrontations between the two came to a head in the summer of 194 when T.E. left home (without his mother’s knowledge or permission). He thought to follow Robert Sonkin1 to New York City. Along the way, he was left behind in Atlanta. Homeless and alone at eleven years of age, his history of the next five years aren’t clear. Later in life he avoided discussing this period beyond uttering that he learned what hungry meant or that he had been thrown out of orphanages, boarding houses and places of ill-repute.. and that his motives for leaving Atlanta came from hearing blues men’s stories of travel.2

Cames eluded to an intimidating late night altercation while traveling alone in the Jim Crow era south that convinced him to migrate north. Though he once joked an angry father ran him out of the south, it seemed more serious than exaggeration and may be the real reason. He spent most of the late 1940’s moving around the Midwest. Too young to join the war campaign, his experiences of World War II were working odd tasks to make due. By the time the Korean War began in 1950, he was working as an errand-man for a younger generation of bluesman. After a number of failed attempts to become a band member with various artists, the rhythmless young man became increasingly bitter as he watched others pass him by. By1956, Cames had given up on the music and was hoping to settle into a slower paced lifestyle.

He moved three or four times, further east with each move, until settling in Pennsylvania, where he worked in a glass factory. This was the first steady period of his life, as he courted and married a young local girl, Maisie Turner, in 1960. He was thirty years old, she was eighteen year-old high school graduate who dreamed of continuing her studies. Given the limited opportunities and her new role as a home maker, she settled on tutoring her undereducated husband. Cames would recall them reading English and history lessons at dinner. In 1968 or 1969, T.E. was injured while operating the plant’s annealing oven. Unable to perform his work with the same speed after the long hospital stay, he was soon laid off. Being out of work was not new to him, but the expectations of his wife were uncompromising. As their financial situation became dire, T.E. and Maisie’s marriage became difficult. He left her one afternoon, taking little more than the money in his pocket and the used car. He seemed fond of her memory, but acted indifferently the few times that he relayed this story to me. Often he ended with a wise crack, like how he had not meant to leave her, he just didn’t find a convenient place to turn the car around. Its unclear if he ever reconciled with her or if he even knew her whereabouts.

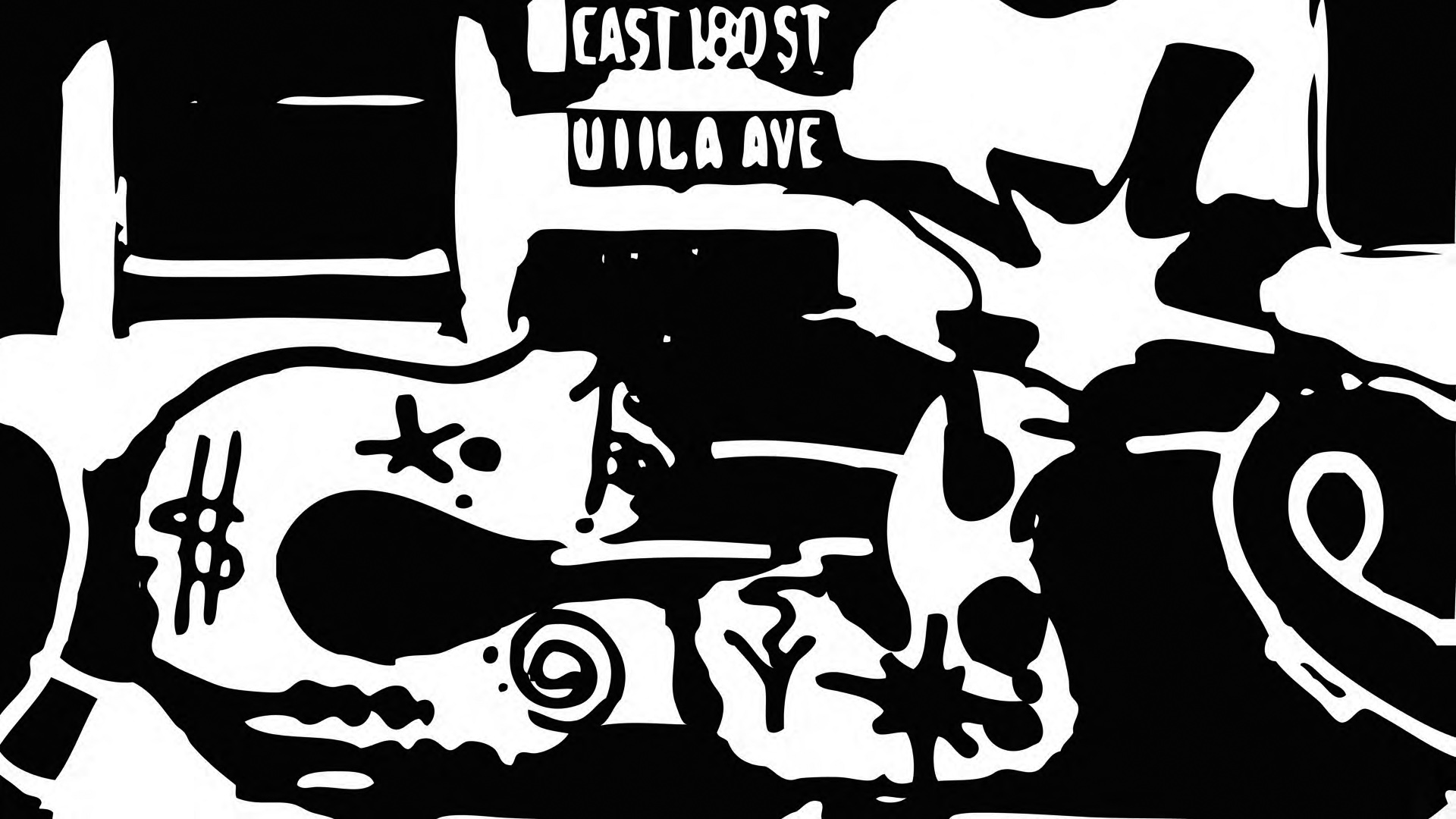

How or why he ended up in New York City is hazy. While he never admitted to such vices, I suspect that he had developed an addiction of some kind and needed to be near a larger concentration of such activity. He was a shady character on this topic, but his actions always suggested there was some validity to the idea. Even late in his life he was never one to turn down a drink, seldom showed the effects if multiple rounds were ordered and oddly didn’t even seem to enjoy them in the process. Not that it appeared like alcohol was an addictive burden; it was more like he had had a real addiction to which the consumption of liquor couldn’t compare. If this speculation is true, it would help explain how a man with a recent blue-collar past (at the time of his arrival in the city) could find himself moving in the circles of reputable pop and graffiti artists by the mid-eighties. Though it is unclear how involved he was in the pop art scene, he would proudly claim to have known Andy Warhol and Keith Haring during this period. I doubt they knew each other as friends, but it is not a stretch that they could be familiar with him, in a similar way to how many of us are acquainted with the doormen, janitors or clerks in our lives only by face, not name. T.E. appears to have played a similar role in this context, as he initially made a living in the city by working social events, mainly as a delivery man, bartender or stagehand. The crowning achievement from this period was an underground spray paint shop that he founded. He was uncharacteristically proud of this endeavor, to the point that he had had a photographer friend produce a large photo of the small place, which he still had at the end of his life.

He loved to assert that he went from being a bartender to art dealer in the sixteen years he spent in New York. It is hard to believe (and there is not any record) that he was an art dealer of any traditional form. Beyond the obvious lack of a cultured background and education in the arts, T.E.’s casual approach seldom left a lasting impression, a clear detriment to any salesman. It is more likely that his claim to the job title comes from a liberal interpretation of his activities around the selling of spray paint to the underground art movement. A prominent example was his assertion that the 1972 City College exhibition on the United Graffiti Artists was his idea. He claimed to have been going around town, that first year in New York, telling everyone who would listen that the subway signings and tags amazed him and were good enough to be in museums. Whether or not any of these conversations were with the actual organizers is unclear.

By the time he left the city in early 1987, T.E. felt that things had changed, or as he would put it: “the scene had turned into a different thing”. But, when asked by a stranger, he always gave the generic answer that he moved west because he was tired of the cold, as though he was a middle-class white man retiring from his office job to sit beside a pool in Phoenix. It is more likely that he was seeking to establish some family connection. His cousin, who was raised by his mother, had lived there, working at a nursing home. His residency in Phoenix would not last; the following year he relocated to the outskirts of Albuquerque, New Mexico. There he bought a small plot of land with a quonset hut on it.

T.E. never had a lot of money and buying property at this point in his life must have been a financial stretch, even if the place was as shabby as the photos suggest. He said that he survived on the profits from gardening. This must have required him to become savvy in tactics of irrigation and growth methods, given the climate and his small plot of land. Whenever he reflected on this time, he did not seem enthusiastic about nature or gardening, initially leading me to suspect that he had been trying to come to terms with his childhood experience with farming. Now I believe he was after something else and the garden was just a necessity.

He took a number of studio art classes at various local institutions., but never sought out a full degree program. His attitude was that you should want to learn something specific, then find the right class or teacher. Whether this was driven by an objective attitude towards production or an avoidance of the academic world, to which he was completely foreign, is up for debate. Regardless, the results were plentiful. Many of the random things that accumulated from these studies made their way with him when he moved north. Like most of the cities in the American southwest, Albuquerque was rapidly expanding during this period. In 2000, T.E. sold his place to a developer, who consolidated it with the neighboring lots and built a strip mall. The offer was just too much money to refuse. T.E. had made a respectable profit, but was without a home at the age of seventy-one.

T.E.’s first cousin once removed lived in Chicago. He had become close to her husband after spending holidays with them in Phoenix. For the second time in his life, he moved across the country to be close to family. Optimistically calculating that he could live another twenty years, he set a strict monthly budget and settled into a small rental unit in a good neighborhood with reputable health care facilities. The first years in town he lived as a retiree, planning daily trips to the museums, park or cinema. But, he grew tired of these things and found a part-time job, working for a glazing contractor. He would spend his mornings around the shop, helping out in whatever way he could. The rest of his daily routine was equally established; lunch and a long nap at home around noon, afternoons spent on errands or at the old desktop computer that a neighbor had given him and, then, evenings passed at the nearby bar or in the park. By the time we had met, he had given up the park as an evening activity. He joked of being mistaken as a homeless man one too many times after falling asleep under a tree. Other than that issue, his control over his active routine was like clockwork. I believe this was the deciding factor that empowered him to take up a new career.

In 2009, T.E. and I opened our architecture practice. He assumed the role of elder partner. Considering that he had no experience with the operations of a functioning architectural practice, (or any kind of professional office, for that matter) his efforts were profound. Shifting between financial and operational planner and self-acknowledged amateur critic, his attitude and approach to problems were refreshingly down to earth, yet sophisticated in a way that only comes from a thoroughly lived life.

The full story of those months working together is better left for another day. But in general, it was a highly rewarding time, even though we have none of the conventional accomplishments that young architectural practices strive for in validating their start-ups. This is not surprising given the casualness to which we began the collaboration. After all, we had started out by working in the local corner bar. It was not until later when our operation ramped up, that he scaled back the number of mornings that he worked at the contractor’s shop, until he completely quit in October of 2010. I had been urging him to do just this six to nine months earlier when he decided to completely give up drinking hard liquor. He may have moved a bit slower at this point, but I was not one to notice. His mind was still sharp, the last time I saw him; a week before he passed.

It was a Monday afternoon in December, when he collapsed outside his apartment door. The stroke was thought to be substantial and made his death fast. The memorial proceedings were equally swift. T.E.’s relatives living in town took care of his arrangements. His modest estate was quickly administered in accordance to an informal handwritten note that he had stored away. Unsure, what to do with his body; his ashes were mailed to his cousin in Phoenix. Thus, all the typical business of T.E. life was thought to be concluded before the beginning of the new year.

The news of his death has spread among his friends at a much slower rate. T.E. had kept a rather compartmentalized network of relationships that made notifying others almost impossible. This fact has created an ongoing saga where those of us who knew him the best at the end are often contacted by others from his days in New York or New Mexico as they discover his death. Their memories of him seem to always cast him in a different light. Making it equally as difficult to objectively understand him in the past tense as it was in the present.